One of the ways we fail to solve problems is by applying simple and wrong solutions to complex problems.

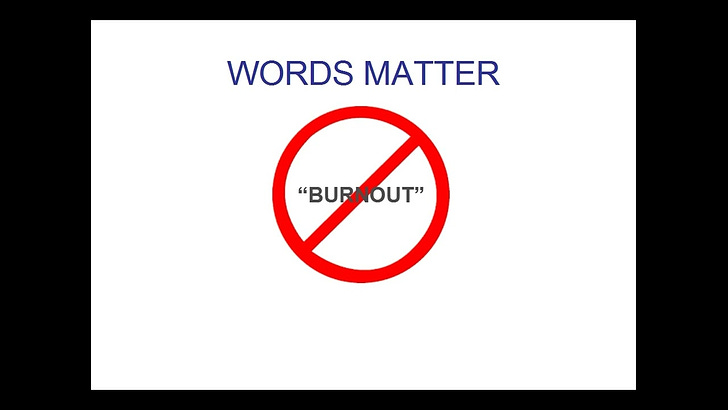

For example, in the case of workplace burnout, organizations have tended to view the problem as consisting of a set of symptoms located INSIDE of people, and have then applied person-centered interventions such as stress management (now mindfulness) training, anti-depressants and EAP/outplacement. People suffering from work strain/exhaustion do look “burned out”, so the term has stuck and guided our thinking and action. The results of this decades-long experiment: the prevalence of burnout is increasing … dramatically.

If you take the time to listen closely to people suffering from burnout, it becomes clear that they are experiencing the end stages of a long and complicated process. Contrary to the popular person-centric model of etiology, burnout is caused largely by multiple interacting vectors that are largely EXTERNAL to the people experiencing the symptoms.

The main drivers of burnout are:

Cultural (watch this space!)

Economic

Technological

Organizational

Professional

Only the “Professional” factor pertains to the people who are experiencing the burnout; the other 4 vectors are external to the people with the symptoms. This means that developing a truly effective intervention/improvement strategy for burnout requires a paradigm shift from focus on the worker to the work ENVIRONMENT. That will involve looking at the organization’s culture among other things.

Got Culture?

One of the most powerful drivers of burnout is also one of the most subtle, complex and hidden, and therefore tends to be overlooked in the search for solutions. That is the matter of the CULTURE of the organization in which people are working.

Culture is one of those vague squishy words that are hard to pin down and therefore create confusion and uncertainty. I like to think of culture as human software that is designed to answer three incredibly important existential questions:

What is real?

What is good?

How do things work?

Human groups (families, communities, organizations, countries) benefit greatly from having clear and credible answers to these critical questions that generate consensus and broad buy-in. Groups that lack unifying cultural software are prone to high levels of conflict and chaos (read: “culture wars”). Chronic cultural conflict drains off precious resources like time and energy that could otherwise be invested in creative activities and success.

Businesses and organizations are not free-standing entities. They are embedded in a local community and a larger nation state. Every community and nation runs cultural software, and that ambient culture usually influences the nature of its organizations’ internal culture. This is because the membrane/boundary between every organization and its external environment is semi-permeable (remember your cell biology course?) and allows things (people, money, equipment, information etc.) to pass in and out.

And this is all well and good. An organization with an impermeable membrane would rapidly lose touch and alignment with the external environment on which its ultimate success partially depends. But the culture outside of an organization is not always an undiluted asset; it can carry disease and illness as well as positive resources as it penetrates the walls of your organization.

History is written by the winners

When the United States “won” the Cold War with the Soviet Union circa 1991, it was more than a military and diplomatic victory. It was also interpreted as a “paradigm” victory. The conflict between the Soviet Union and the industrialized nations of Europe and North America was often framed as a competition between so-called free markets (capitalism) vs. government controlled economies (communism).

Leaving aside the question of whether there is really such a thing as a “free” (unregulated) market, the collapse of the Soviet economy was attributed, not without merit, to the view that when people are not free to create enterprises and to benefit financially from their success, they lose the main motivating engine of economic activity as measured by GDP. Within this framework, winning the Cold War was interpreted as the ultimate validation of the market (for-profit) economy as the “right” economic model. It would not be an overstatement to say that we have seen a pretty significant level of proselytizing and evangelization of the benefits of a market economy over the past 30 years.

It’s the economy … STUPID!

Economically under-performing countries are now generally advised to increase productivity and decrease government support programs (“taking a haircut”) to jump start growth. The World Bank and other institutions have prescribed various forms of “shock therapy” with elements of austerity and deregulation to stagnant economies in return for some degree of new loans and/or debt relief.

People working in not-for-profit organizations are told that they need to operate more like a “real” (for-profit) business, even though their funders often refuse to cover their real operating (indirect) costs, thereby putting them at an economic disadvantage. So the market economy model is feeling pretty superior and puffed up these days, and is acting with bold swagger and towering confidence.

To get rich is glorious. — Deng Xiaoping

It is one thing to have a market ECONOMY that prescribes certain values and beliefs and practices for its business organizations. But we have moved beyond this to what could be called a market SOCIETY in which those beliefs, values and practices have metastasized to take over the social sphere as well. More and more, our national culture answers the 3 big existential questions as follows:

What is real: business and the balance sheet

What is good: profit, capital, entrepreneurship

How do things work: survival of the “fittest” (read: biggest, best capitalized, closest to monopoly status)

People and activities, both in and out of the workplace, are evaluated more and more in terms of their economic ROI. Our cultural icons are successful businesses and their founders and CEOs and investors. Children dream more and more of starting businesses and being the next billionaire. Government and its programs are evaluated more in terms of how “business friendly” they are rather than how well they serve the needs and interests of the broader citizenry and commons.

This is the ultimate victory of the market economy: it penetrates every social institution with its cultural values, beliefs and practices.

Human labor as cost vs. asset

Labor is the true standard of value. Labor is prior to, and independent of, capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration. — Abraham Lincoln

One real world implication of this paradigm shift relates to our attitude toward people and their work/labor. In the market paradigm, profits can be generated by increasing revenues and decreasing costs/overhead. On the balance sheet, people and their salaries are always tallied as a COST, and therefore something to be reduced.

Reduced labor costs can be achieved by three familiar strategies: increased efficiency (do more work with the same/fewer people), outsourcing work to lower cost labor markets, and automation/AI. Employers have made increasing use of all three of these people/labor cost reduction methods vigorously since the end of the Cold War. Recessions are viewed as opportunities to strip away labor costs by these means, creating “jobless recoveries”. It is what a market culture prescribes and applauds.

In a market economy/society, the ideal labor market is one where workers are paid as little as possible, can not say “No” to more work, and can’t leave the workplace. These characteristics of course achieved their most pure expression in the slave plantation. More and more people working in market economies/societies are noticing that there is strong downward pressure on their wages, they are too job insecure to dare to refuse any demands from their boss, and they find it harder and harder to leave work and go home at a reasonable hour. They are feeling the relentless forces of a market economy/society/culture.

Feel the burn …

When environmental demands exceed a person’s adaptive capacity (energy, cognitive/executive functioning) limits, and the person is unwilling or unable to leave that environment (physically) or disengage (mentally), they will begin to show the familiar symptoms of stress and burnout (exhaustion, demoralization, physical pain/illness).

Even before the time-motion studies that gave rise to the “modern” piece-work/assembly line production model, employers discovered they could squeeze ever more output per unit person/time. Escalating demands for greater efficiency/output will ultimately result in human illness and even death, but this can be written off as a cost of doing business. We currently see soaring rates of burnout among workers in many sectors, and even among our school-aged children as they struggle to prepare themselves to enter the job market. The victory of the market society/culture has normalized working beyond one’s adaptive capacity, and makes it harder for people to feel entitled to protest or push back.

Even when leaders propose mission models that extend beyond a unitary focus on profit (e.g. the corporate “triple bottom line”; the “triple aim” in healthcare), the non-financial elements (customers, community, environment etc.) mostly do not include the people who do the work. That silence speaks volumes about what we value and hold dear. This cultural neglect of the people who do the work will likely continue until enough people begin to seriously question the relative benefits and costs of our modern market society, and propose a valid alternative that provides some protective immunity against the epidemic of oppressive work.

And, inasmuch [as] most good things are produced by labor, it follows that [all] such things of right belong to those whose labor has produced them. But it has so happened in all ages of the world that some have labored, and others have, without labor, enjoyed a large proportion of the fruits. This is wrong, and should not continue. To [secure] to each laborer the whole product of [their] labor, or as nearly as possible, is a most worthy object of any good government. — Abraham Lincoln

This is an insight rich article. I see culture at the core of who we are, or aren't. These days, I'd call our respective cultures confused with impermeable borders. We have trouble defining ourselves and the old culture of reaching out to others to collect new ideas has atrophied. Thank you for writing down your thoughts and reaching out with them.

Amazing that Abraham Lincoln, an American President, said that last paragraph. How the US has strayed from his wisdom.